Literacy is declining across all demographics in the United States.1

All demographics measured. Men and women. All age groups. All levels of education.

If you live in the United States, you likely already suspected this phenomenon. Same here. Maybe you don’t need to legitimize your suspicions by surfing survey results but I do! So, I spent the last week riding waves of disappointing data so that you wouldn’t have to, you can thank me later.

“Literacy is declining,” ok but wdym

What does it mean to say, “literacy is declining?” People aren’t forgetting how to read, are they? No. Literacy is not an on/off switch. It’s a spectrum and it’s possible to traverse this spectrum, throughout life, in either direction. Literacy is a skill that requires maintenance.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines literacy as, “a continuum of learning and proficiency in reading, writing and using numbers throughout life,” and “part of a larger set of skills, which include digital skills, media literacy, education for sustainable development and global citizenship as well as job-specific skills.”2

Another, more modern definition of literacy comes from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC). PIAAC defines literacy as “accessing, understanding, evaluating, and reflecting on written texts in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to participate in society.”3

PIAAC defines literacy as “accessing, understanding, evaluating, and reflecting on written texts in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to participate in society.”

Two hundred years ago, only one in ten people across the globe could read. Now, the reverse is true. 90% of the world’s population is literate as a result of education efforts across generations and borders.4 Granted, two hundred years is a generous timeline for change, still, I find this progress impressive especially given the scale of impact.

If what was most important for literacy in the 1800s was expanding basic education to all, today, priorities are more complex. Information flows like water. It’s downloadable, easily decipherable, and yet, sometimes deceiving. Readers today need to know more than spelling and grammar to participate in society and achieve one’s goals.

Today’s bar of literacy is elevated by the twin notches of evaluation and engagement. As we’ll see, these are the elements of literacy that have drifted out of reach for many in recent years. I would love to see our society move towards participation and collaboration over the fragmentation I’ve witnessed throughout my life. To this end, time spent examining and striving to improve literacy seems to be worth our while.

Now, to the data!

PIAAC Survey Results: United States

As we saw, the rise of global literacy took centuries, however, there were seasons of relatively quick change within those years. A disproportionate amount of progress was made between 1980 and 2000 when the international literacy rate spiked from 56% to 80%.5 The decline in literacy we’ll be focusing on today also transpired over a relatively short timeframe, the decade between 2014 and 2024.6

The most abundant statistics I could find on American literacy came from PIAAC, the “cyclical, large-scale study of adult cognitive skills and life experiences.”7 Conducting this study is indeed an enormous effort with a robust website to match the undertaking. The companion site offers more information on sample questions, methodologies, and other publications related to the data.8

In their words, PIAAC exists “to allow cross-cultural and international comparisons of results of skill-formation systems and their outcomes,” “to allow countries to […] administer the survey in their national languages while still obtaining internationally comparable results,” and “as a survey that will be repeated over time to allow policy makers to monitor the development of key aspects of human capital in their countries.”9

PIAAC measures literacy across the world by providing adaptive exercises for sample groups of adults between the ages of 16 and 65 representing over 1 billion people across dozens of countries.1011 The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) is responsible for facilitating the survey in the United States.

PIAAC Levels of Proficiency

To understand the recent decline in literacy, I think it’s helpful to start by looking at how PIAAC ranks literacy according to their 500 point scale across six levels of proficiency.12

Below Level 1 (0-175 points)

Below Level 1 survey participants can read simple paragraphs, evaluate plausibility and complete simple tasks related to the text as long as they’re given explicit instructions. The existence of this category implies everyone (or nearly everyone?) surveyed by PIAAC would likely be considered literate by Oxford Dictionary’s inclusive standard of literacy, stated simply as, “the ability to read and write.”13 However, by PIAAC standards, literacy proficiency begins at Level 3, suggesting adults at all proficiency levels below Level 3 are considered to be at least “partially illiterate.”14

Level 1 (176-225 points)

At the first level of proficiency are adults with the ability to locate information within text, comprehend the meaning of short texts, and identify relevant passages when given multiple options and explicit cues. Level 1 texts are usually single page texts comprised of a few hundred words, without distracting information. Tasks at Level 1 are “fairly obvious” matches between a question and target information within a text.

Level 2 (226-275 points)

We see adults at Level 2 that can understand longer texts, including distracting information. They can paraphrase and they can navigate slightly more complex digital environments than those at Level 1. Tasks at Level 2 might have lengthy instructions or introduce participants to “unfamiliar situations” such as performing tasks without strong guidance.

Level 3 (276-325 points)

Adults at Level 3 are able to combine multiple skills such as accessing, understanding, inferring, comparing, and evaluating information, when completing tasks. Level 3 texts are lengthier than those of Levels 1 and 2 and may be pulled from sources with conflicting information.

Level 4 (326-375 points)

Level 4 builds on the demands of Level 3, presenting participants with abstract or lengthy content that includes large amounts of distracting information. Tasks at this level require adults to access, understand, evaluate and reflect on texts from multiple sources while inferring what’s needed for the task from implicit statements.

Level 5 (376-500 points)

The final level of proficiency, Level 5, shows adults capable of designing tasks and creating reading goals to achieve them based on complex requests. They exhibit advanced skills in navigating extensive catalogs, complex menus, and unstructured search results to synthesize information, contrast ideas, and evaluate evidence-based arguments as well as the reliability of unfamiliar information sources. Readers at Level 5 select information that is not just topically relevant but also trustworthy.15

Deets on the Decline

When PIAAC completed the first cycle of surveys in 2014, the average American scored near the upper boundary of Level 3 proficiency. Ten years later, American adults suffered a significant drop in average proficiency as 2024 results showed the average American now hovering near the middle of Level 2 proficiency. Recall, according to PIAAC, literacy proficiency begins at Level 3.

Americans seems to be falling at a worrying rate into illiteracy as shown by Level 1’s greedy consumption of adults over the last decade. In 2014, only 18% of Americans sat at Level 1 proficiency or below. Today, 28% of Americans are at Level 1 or below! Apparently, many of us have lost the ability to stick with lengthy texts and perform basic evaluations of information. 57% of American readers are now distributed across the lowest levels and are considered at least “partially illiterate.”16

PIAAC Survey Results: Other Countries

A not-so-fun fact: literacy isn’t just declining in the United States, it’s also stagnating across the world. Of course, Denmark and Finland are exempt from the trend (shocking no one).

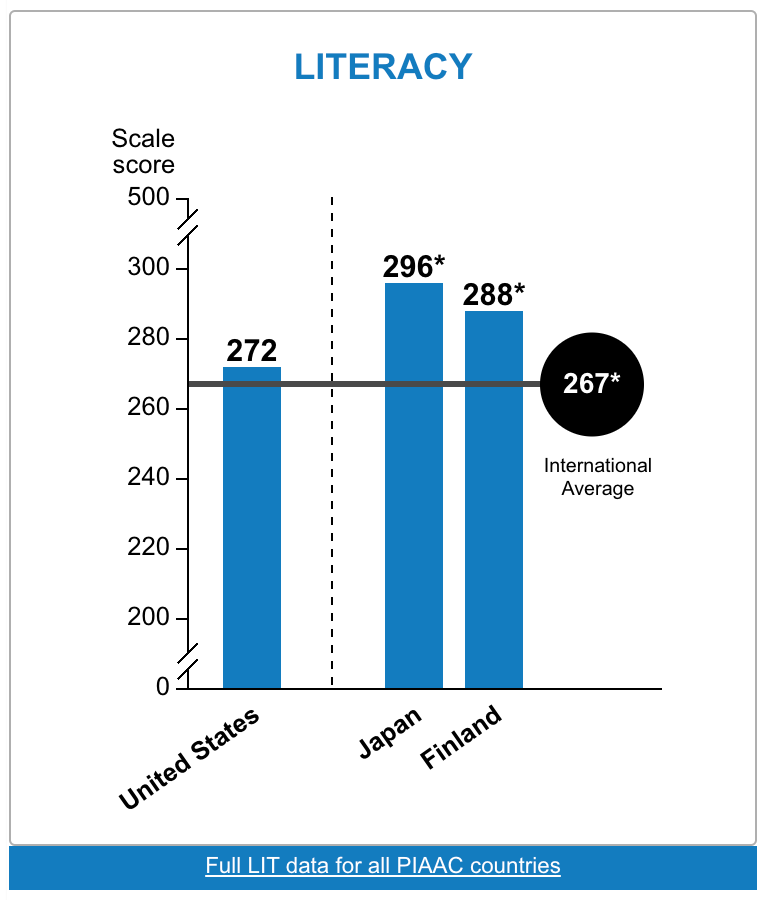

31 countries were included in the most recent PIAAC survey cycle and average international literacy proficiency was found to be 267, near the upper limit of Level 2 proficiency.17 The United States’ average literacy proficiency is 272, just above the international average. Again, worth nothing, both the international average and the United States average proficiency scores are in the “partially illiterate” realm of Level 2 according to PIAAC.

In contrast, Japan’s and Finland’s average scores are 296 and 288, respectively. Both of these scores are in the mid Level 3 proficiency range, meaning the average reader in Japan or Finland would be considered literate by PIAAC standards.

Aside from Denmark and Finland, Sweden, Norway, Estonia, and the Flemish Region of Belgium recorded modest increases in literacy proficiency over the last decade. While Japan, the Netherlands, England, Canada, Ireland, Czechia, France, Singapore, Spain, Italy, and Chile recorded modest decreases. Places where literacy decreased dramatically were New Zealand, the United States, Austria, Slovak Republic, Korea, and Lithuania.

The countries with the highest average literacy proficiencies, aside from Finland and Japan as discussed above, are Sweden, Norway, and the Netherlands. These countries’ average readers would all be considered proficient at Level 3 or above.

Why does literacy proficiency matter?

Now that we have a pretty solid sense of what literacy is, where the United States stands as a literate population, and how the rest of the world is doing, we can get to the fun part. Why does any of this matter?

How does literacy impact communities and economies? What are the outcomes of highly literate populations versus ones that are less so? Does reading fiction lead to unique outcomes? What is reading’s effect on the brain? Why does reading tend to connote a higher “morality” than other mediums of information?

I can’t wait to dive into these questions this week! I’ll see you next Sunday with the scoop.

Japan…. Always taking the W